Breakthrough Gene Editing Therapy Shows Early Success Reversing Inherited Blindness in a First-of-Its-Kind Human Trial

A pioneering gene editing therapy has produced early signs of restored vision in people with inherited blindness. Researchers tested a CRISPR-based approach designed to correct a specific disease-causing mutation in the eye. The first-in-human intraretinal editing trial offers a powerful proof of concept. Preliminary findings show functional gains for some participants, alongside a favorable early safety profile. Momentum is building as teams refine dosing, selection, and measurements.

The Target: A Severe Form of Inherited Blindness

The study focuses on Leber congenital amaurosis type 10, commonly called LCA10. LCA10 stems largely from a mutation in the CEP290 gene. The most frequent variant disrupts normal RNA splicing and impairs photoreceptor function. Affected individuals often present with severe vision loss in early life. Therefore, researchers pursued a precise edit that could restore normal gene function in retina cells.

This target offered a compelling rationale for a localized, one-time intervention. The eye’s immune environment and accessibility further support this approach. Investigators could deliver editing tools directly to diseased photoreceptors. They planned careful monitoring of visual function and retinal structure. These factors created a strong foundation for a first-of-its-kind study.

The Editing Strategy: Removing a Harmful Genetic Roadblock

The therapy uses CRISPR to remove a small piece of DNA that causes the splicing error. This deletion aims to restore proper CEP290 messenger RNA production in photoreceptors. Researchers designed guide RNAs that target sequences flanking the mutation. The CRISPR enzyme then cuts the DNA at precise spots, enabling correction by deletion. The strategy seeks permanent correction in edited cells.

Scientists optimized the components to limit off-target editing. They also validated editing in cells and animal models before human dosing. The team prioritized safety and efficiency during development. Precise cutting and localized delivery supported that objective. The design reflects years of preclinical refinement and testing.

Delivering the Treatment: Surgery and Vector Technology

Surgeons deliver the gene editor by subretinal injection. This approach places the therapy directly under the retina near target photoreceptors. The CRISPR machinery travels in an engineered adeno-associated virus vector. This vector type shows strong retinal tropism and sustained expression. The localized delivery helps limit exposure to the rest of the body.

Subretinal delivery requires a brief, specialized procedure in an operating room. Retinal surgeons create a controlled retinal detachment called a bleb. They then inject the vector solution into that space. The bleb reattaches as fluid clears. Experienced teams perform these procedures routinely for other ocular therapies.

The Trial: A Structured Phase 1/2 Study With Careful Endpoints

The BRILLIANCE study evaluates safety, dosing, and preliminary efficacy in adults and children. The sponsor initially included Editas Medicine alongside an early collaborator. Investigators enrolled participants with confirmed CEP290-associated LCA10. Dosing follows a standard escalation plan with close safety monitoring. The primary endpoint focuses on safety, with multiple efficacy assessments as secondary endpoints.

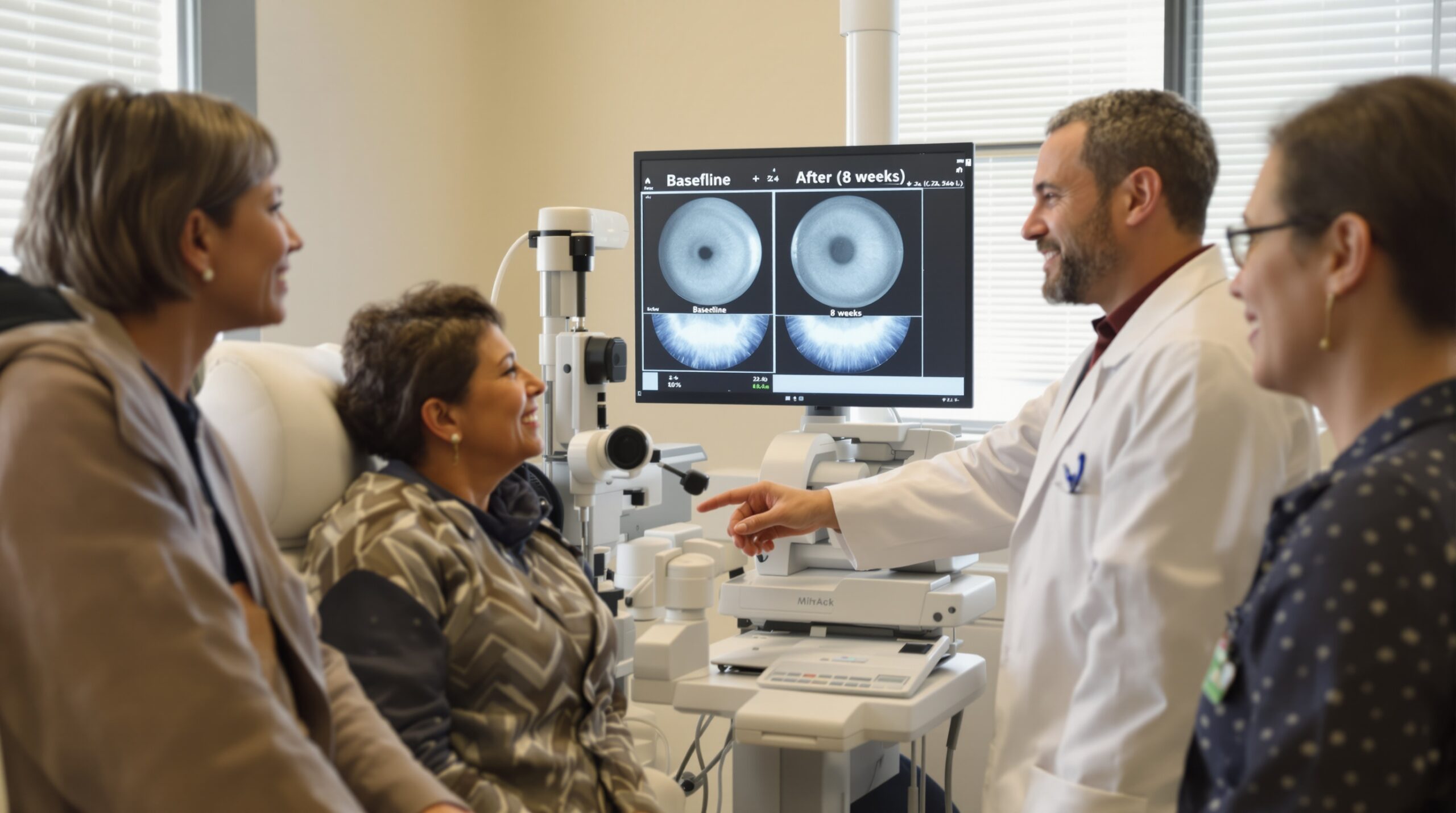

Researchers used standardized tests of visual function to track changes over time. They measured best-corrected visual acuity and light sensitivity. Teams also assessed navigation in low-light mobility tasks. Imaging studies evaluated retinal structure and photoreceptor layers. Together, these measurements provided a comprehensive efficacy picture.

Early Results: Safety Signals and Functional Gains

Early readouts show an encouraging safety profile. Investigators reported no dose-limiting toxicities across the early cohorts. Eye inflammation and surgery-related effects remained manageable with standard treatments. Off-target editing assessments have not signaled concerning findings to date. Overall, safety data supported continued study progress and exploration of dosing.

Preliminary efficacy signals also emerged in several participants. Some showed improved light sensitivity on full-field stimulus testing. Others demonstrated better visual acuity measurements from baseline. Participants also navigated mobility courses faster and with fewer errors. These gains suggest meaningful real-world improvements for select individuals.

Interpreting the Magnitude of Improvement

The magnitude of benefit varied among participants. Not every individual experienced measurable improvements on every test. That variability is common in early-stage gene therapy trials. Small cohorts and diverse baseline function can influence outcomes. Continued follow-up will clarify durability and refine expectations for response rates.

Investigators emphasize cautious optimism as data mature. Longer observation can reveal trends that early snapshots miss. Additional dose levels may boost editing efficiency and responses. Better baseline stratification could identify individuals most likely to benefit. Ongoing analysis will guide those adjustments thoughtfully.

How This Differs From Existing Vision Therapies

This therapy edits DNA rather than supplementing a missing gene. A prior approved therapy, Luxturna, augments the RPE65 gene. In contrast, the current approach removes a specific harmful sequence in CEP290. Editing aims for a one-time, permanent fix in targeted cells. That distinction carries both opportunities and responsibilities for safety monitoring.

Gene augmentation can face size limits for vectors. The CEP290 gene exceeds common vector capacity for full replacement. Editing avoids that constraint by correcting endogenous DNA. The method therefore expands the range of treatable genetic diseases. It also must balance precision with thorough long-term surveillance.

What Patients May Notice After Treatment

Patients may detect improved light perception or contrast sensitivity first. Some may notice better navigation in dim environments. Others could read more lines on a vision chart than before. These changes often arrive gradually as photoreceptors recover function. Supportive rehabilitation can help individuals translate gains into daily activities.

Clinical teams schedule frequent follow-up visits after surgery. They repeat standardized tests to capture trends precisely. Imaging helps verify structural changes consistent with functional gains. Careful documentation informs future patient counseling and selection. Shared decision-making remains central throughout the process.

Scientific Significance: A Milestone for In Vivo Editing

This trial demonstrates that in vivo CRISPR editing can produce functional improvements in humans. The eye provides a valuable proving ground. Success here supports broader applications in other tissues. Lessons from vector design, dosing, and delivery will inform next-generation strategies. The field now has human evidence beyond animal models.

The results also validate correcting splicing defects directly in affected cells. That approach may generalize to many inherited diseases. Researchers already explore editing for different retinal conditions. Additional programs target genes implicated in retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease. Incremental progress can expand access to genetic vision restoration.

Limitations and Challenges That Remain

The study includes small cohorts and variable baselines. That reality limits firm conclusions about average effect sizes. Editing creates mosaic correction across treated cells, not uniform changes. Some photoreceptors may be too damaged to recover meaningful function. Surgical delivery also concentrates edits within a defined region.

Immune responses to the viral vector can occur, although generally manageable. Retinal detachment during surgery remains a theoretical risk. Off-target editing requires continued surveillance with sensitive assays. The durability of benefit needs longer follow-up across participants. Each factor informs responsible development and oversight.

Ethical Safeguards and Patient Protections

Ethics committees reviewed the trial’s risk-benefit profile rigorously. Investigators obtained informed consent and assent where applicable. Monitoring boards oversee safety and data integrity throughout. Data sharing follows established standards for transparency and accountability. These safeguards protect participants while enabling scientific progress.

Researchers also prioritize equitable access considerations. Genetic testing and counseling help identify eligible candidates. Patient registries support fair recruitment and diverse participation. These systems will guide future deployment if approvals eventually occur. Aligning innovation with fairness remains essential for public trust.

What Comes Next for the Program and the Field

Investigators plan longer follow-up and potential dose optimization. They will refine patient selection using baseline function and imaging. New delivery systems could expand the treated retinal area. Nonviral delivery and improved editors may enhance precision. Combination strategies might pair editing with neuroprotective agents.

Regulators will require robust safety and efficacy evidence before approval. Future studies may include randomized, controlled components where feasible. Manufacturers must also address scale, cost, and access challenges. Training more surgeons in consistent delivery will be crucial. Each step will shape the path toward broader availability.

The Bottom Line

Early results from this first-of-its-kind eye editing trial show cautious but real progress. Safety data remain encouraging across studied cohorts. Several participants experienced measurable improvements in vision-related function. Those gains provide hope for people living with inherited blindness. They also mark a milestone for therapeutic genome editing in humans.

The journey from first signals to routine care takes time. Science will refine methods and clarify who benefits most. Continued collaboration will speed answers and responsible adoption. For now, the field has crossed an important threshold. Vision restoration through precise gene editing looks increasingly achievable.