Scientists have mapped a vast microbial ecosystem beneath Antarctic ice sheets, revealing a thriving world in darkness. This concealed biosphere metabolizes ancient carbon, recycles nutrients, and interacts with subglacial water flowing to the ocean. The discovery challenges assumptions about life’s limits and underscores Antarctica’s dynamic role in Earth’s biogeochemistry. It also spotlights how cold, isolated habitats can influence atmospheric greenhouse gases. These revelations connect polar subsurfaces to processes that reach across the globe.

Antarctica’s subsurface remained elusive due to extreme conditions and thick, crevassed ice. Yet geophysical surveys and carefully sterilized boreholes now trace networks of lakes, streams, and saturated sediments. Microbial communities inhabit these zones, feeding on minerals, dissolved gases, and buried organic matter. Their metabolism produces and consumes carbon compounds, balancing chemistry across great distances. Understanding this balance offers a new lens on climate feedbacks.

The mapping effort integrates multiple strands of evidence into a coherent picture. Researchers combine radar, seismic, and electrical imaging with geochemical measurements and genetic analyses. The approach reveals connected habitats rather than isolated pockets of life. It also illuminates pathways that shuttle carbon between bedrock, ice, and the ocean. These connections reframe the Antarctic interior as a dynamic, living system.

The Hidden World Beneath the Ice

Subglacial environments include buried lakes, pressurized channels, and porous sediments below the ice base. Moving ice grinds rock into fine flour, creating reactive surfaces for microbial energy. Pressure keeps water liquid at temperatures well below freezing. Dissolved salts and geothermal heat maintain habitable niches for persistent microbial activity. These conditions support ecosystems shielded from surface extremes.

Water flows episodically along the bed, linking basins through hidden drainage pathways. When lakes fill and drain, they transport cells, nutrients, and reduced compounds downstream. Such pulses can reorganize microbial communities and chemical gradients. They also export subglacial carbon to the continental margin. Downstream effects connect ice sheet interiors to the Southern Ocean’s productivity and carbon uptake.

How Scientists Mapped the Subglacial Biosphere

Ice-penetrating radar traced water bodies by detecting smooth, reflective basal interfaces. Seismic surveys estimated sediment thickness and porosity beneath grounded ice. Electrical and electromagnetic methods revealed zones of high conductivity, consistent with brines and wet sediments. Satellite altimetry recorded subtle surface elevation changes from lake filling and drainage. These independent tools delineated a connected hydrological network.

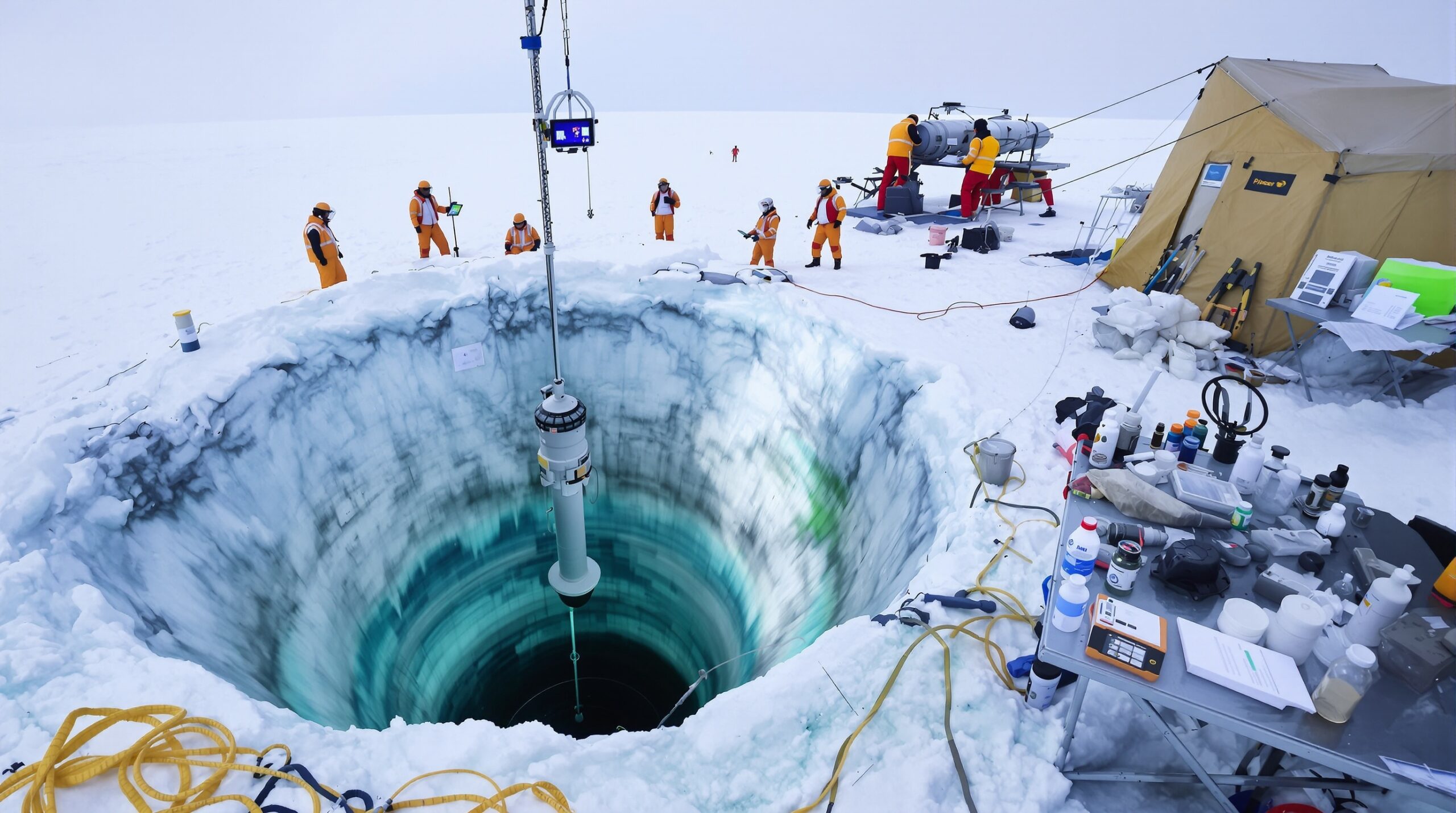

Teams accessed select sites using sterile, hot-water drilling systems. They retrieved water, sediments, and ice samples for microbiological and geochemical analysis. Metagenomic sequencing characterized metabolic pathways present within the communities. Isotopic measurements traced carbon sources and microbial processing rates. Together, these methods linked structure, function, and flux.

Who Lives There and How They Survive

Microbial residents include bacteria and archaea adapted to cold, dark, and oxygen-limited environments. Many oxidize reduced iron, sulfur, or hydrogen liberated from crushed minerals and bedrock. Others ferment buried organic material left from earlier climatic periods. Methanogens generate methane from carbon dioxide and hydrogen under strict anoxic conditions. Methanotrophs then consume methane when oxidants become available.

This metabolic diversity stabilizes resource use across shifting hydrological regimes. When water drains, anaerobes thrive within isolated, low-oxygen pores. When oxidants pulse through channels, aerobic taxa bloom and oxidize reduced compounds. Communities cycle between these states without collapsing. Such resilience sustains persistent carbon processing beneath the ice.

Rewriting Antarctica’s Role in Carbon Cycling

Subglacial microbes transform carbon between organic and inorganic forms in situ. They store carbon as biomass and extracellular polymers within sediments. They release dissolved organic carbon that flows into downstream waters. They also generate carbon dioxide through respiration and produce methane under anoxic conditions. These processes shape greenhouse gas potentials from ice-covered landscapes.

Not all carbon becomes atmospheric. Some carbon binds to minerals and remains buried in sediments. Iron released from bedrock can complex organic carbon, reducing microbial decomposition rates. This mineral association may sequester carbon for long timescales. Such storage offsets some emissions from subglacial respiration.

Subglacial waters deliver iron, silica, and other micronutrients to coastal seas. These nutrients can stimulate phytoplankton blooms in nutrient-limited Southern Ocean regions. Enhanced photosynthesis draws carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into surface waters. Sinking organic matter then moves carbon to deeper layers. Thus, subglacial exports can indirectly support oceanic carbon sequestration.

Methane dynamics add another layer of complexity. Methanogens create methane in reducing pockets within sediments and channels. Downstream oxidation can consume a significant share before escape. However, rapid drainage events may outpace microbial oxidation capacity. These episodes could intermittently vent methane to the ocean and atmosphere.

The balance among production, consumption, and export determines net climate effects. It likely varies across regions and hydrological states. Some areas may act as net carbon sources under rapid drainage. Others may act as sinks through mineral stabilization and ocean fertilization. Ongoing measurements will refine these regional budgets.

Climate Feedbacks and Ice Sheet Change

Warming oceans and shifting winds influence grounding lines and subglacial hydrology. Increased basal melt can expand water pathways and habitat extent. Faster ice flow may enhance rock comminution and chemical weathering rates. These changes alter energy supplies for microbial metabolisms. They also modify the timing and magnitude of carbon exports.

Climate models increasingly incorporate biogeochemical feedbacks from high latitudes. Subglacial processes should join these representations as observational constraints strengthen. Better coupling will improve projections of greenhouse gas trajectories. It will also refine estimates of Southern Ocean carbon uptake capacities. Integration requires collaboration across glaciology, microbiology, and oceanography.

Uncertainties and Research Gaps

Significant uncertainty remains in scaling local observations to continental extents. Sampling remains rare, expensive, and logistically challenging. Many communities likely remain unsampled beneath thick, fast-moving ice. Fluxes also vary strongly over time, complicating annual budgets. These factors require cautious interpretation of net climate impacts.

Methodological constraints add further complexity. Drilling can disturb delicate gradients and introduce oxygen pulses. Waste heat may temporarily alter microbial activity near boreholes. Researchers therefore triangulate with noninvasive geophysics and modeling. Cross-validation strengthens confidence in inferred processes and rates.

Tools Transforming Polar Biogeochemistry

Autonomous sensors now measure chemistry within subglacial channels and outlets. Instruments track oxygen, redox potential, dissolved organic carbon, and trace metals. Uncrewed vehicles explore water-filled cavities and grounding zones under floating ice. Fiber-optic cables can monitor temperature and strain along boreholes. These technologies extend observations beyond short field campaigns.

Advances in environmental genomics reveal active metabolisms in situ. Metatranscriptomics highlights genes expressed under fluctuating redox conditions. Stable isotope probing links specific taxa to carbon transformations. New bioinformatics tools distinguish resident microbes from contaminants. Together, these approaches clarify who does what, where, and when.

Connecting the Interior to the Ocean

Subglacial outflows mix with shelf waters and circulate along coastal currents. These plumes carry dissolved carbon, nutrients, and suspended sediments offshore. Ocean mixing and light availability govern downstream biological responses. Iron-rich inputs can spark blooms that draw down carbon dioxide. Yet excess light limitation can mute fertilization effects in winter.

Tracing these linkages requires coordinated observations from ice to open ocean. Gliders and floats can follow plumes and quantify carbon flux changes. Moorings measure seasonal variability beneath sea ice cover. Satellite ocean color monitors phytoplankton responses when conditions allow. These datasets tie subglacial dynamics to marine carbon sequestration.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

Global carbon budgets depend on accurate accounting across all major reservoirs and pathways. Antarctica’s hidden ecosystems represent a previously underappreciated term. Their inclusion can shift our understanding of polar feedbacks on atmospheric composition. It also informs stewardship of a region sensitive to climate change. Evidence-based policy needs such integrated, mechanistic insights.

As ice sheets evolve, their biogeochemical roles will also change. Early detection of new outflow routes can guide monitoring priorities. Adaptive surveys can track emerging hotspots of carbon processing. Open data practices will accelerate model improvements across disciplines. The community now possesses tools to meet this challenge.

Looking Ahead

Future work will map habitats across broader sectors and seasons. Researchers will quantify fluxes during both quiescent and drainage phases. Experiments will test how warming and hydrological shifts alter metabolisms. Models will assimilate observations to estimate net impacts on atmospheric carbon. Each step will refine confidence in projected feedbacks.

The emerging picture is compelling and consequential. Antarctica’s subglacial biosphere is not a passive, frozen archive. It is an active agent in global carbon cycling and climate. Continued mapping and measurement will reveal its changing influence. The planet’s coldest places are more connected than we imagined.